What Style of Art Was Paul Klee Known for What Style Was Paul Klee Known for

| Paul Klee | |

|---|---|

Paul Klee in 1926 | |

| Born | eighteen December 1879 Münchenbuchsee, Switzerland |

| Died | 29 June 1940(1940-06-29) (anile 60) Muralto, Switzerland |

| Nationality | German |

| Education | Academy of Fine Arts, Munich |

| Known for | Painting, drawing, watercolor, printmaking |

| Notable piece of work | More than x,000 paintings, drawings, and etchings, including Angelus Novus (1920), Twittering Machine (1922), Fish Magic (1925), Viaducts Break Ranks (1937). |

| Movement | Expressionism, Bauhaus, Surrealism |

Paul Klee (German: [paʊ̯l ˈkleː]; 18 December 1879 – 29 June 1940) was a Swiss-built-in German language artist. His highly private style was influenced by movements in fine art that included expressionism, cubism, and surrealism. Klee was a natural draftsman who experimented with and eventually deeply explored color theory, writing about it extensively; his lectures Writings on Form and Blueprint Theory (Schriften zur Form und Gestaltungslehre), published in English as the Paul Klee Notebooks, are held to be as of import for modern art every bit Leonardo da Vinci'due south A Treatise on Painting for the Renaissance.[1] [2] [three] He and his colleague, Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky, both taught at the Bauhaus schoolhouse of art, design and architecture in Germany. His works reflect his dry out humor and his sometimes artless perspective, his personal moods and beliefs, and his musicality.

Early on life and preparation [edit]

First of all, the art of living; then as my ideal profession, poetry and philosophy, and every bit my real profession, plastic arts; in the last resort, for lack of income, illustrations.

—Paul Klee[4]

Paul Klee was born in Münchenbuchsee, Switzerland, as the 2d kid of German music teacher Hans Wilhelm Klee (1849–1940) and Swiss vocaliser Ida Marie Klee, built-in Frick (1855–1921).[a] His sister Mathilde (died 6 December 1953) was born on 28 January 1876 in Walzenhausen. Their father came from Tann and studied singing, piano, organ and violin at the Stuttgart Conservatory, where he met his time to come wife Ida Frick. Hans Wilhelm Klee was active as a music instructor at the Bern State Seminary in Hofwil most Bern until 1931. Klee was able to develop his music skills as his parents encouraged and inspired him throughout his life.[v] In 1880, his family moved to Bern, where they somewhen, in 1897, after a number of changes of residence, moved into their own house in the Kirchenfeld commune.[6] From 1886 to 1890, Klee visited chief school and received, at the age of seven, violin classes at the Municipal Music School. He was and then talented on violin that, aged 11, he received an invitation to play as an extraordinary fellow member of the Bern Music Clan.[7]

My Room (German: Meine Bude), 1896. Pen and ink launder, 120 by 190 mm (4+ three⁄4 past 7+ i⁄two in). In the drove of the Klee Foundation, Bern, Switzerland

In his early on years, post-obit his parents' wishes, Klee focused on becoming a musician; but he decided on the visual arts during his teen years, partly out of rebellion and partly considering modern music lacked meaning for him. He stated, "I didn't detect the thought of going in for music creatively particularly attractive in view of the decline in the history of musical achievement."[8] Every bit a musician, he played and felt emotionally bound to traditional works of the eighteenth and nineteenth century, but as an creative person he craved the freedom to explore radical ideas and styles.[viii] At sixteen, Klee'southward landscape drawings already testify considerable skill.[9]

Effectually 1897, Klee started his diary, which he kept until 1918, and which has provided scholars with valuable insight into his life and thinking.[ten] During his school years, he avidly drew in his school books, in particular drawing caricatures, and already demonstrating skill with line and book.[eleven] He barely passed his concluding exams at the "Gymnasium" of Bern, where he qualified in the Humanities. With his characteristic dry wit, he wrote, "Afterward all, it's rather hard to achieve the verbal minimum, and it involves risks."[12] On his own time, in improver to his deep interests in music and art, Klee was a keen reader of literature, and subsequently a writer on art theory and aesthetics.[13]

With his parents' reluctant permission, in 1898 Klee began studying art at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich with Heinrich Knirr and Franz von Stuck. He excelled at drawing but seemed to lack whatever natural color sense. He later recalled, "During the tertiary wintertime I even realized that I probably would never acquire to paint."[12] During these times of youthful take chances, Klee spent much time in pubs and had diplomacy with lower-course women and artists' models. He had an illegitimate son in 1900 who died several weeks subsequently nativity.[14]

Afterwards receiving his Fine Arts degree, Klee traveled in Italy from Oct 1901 to May 1902[15] with friend Hermann Haller. They visited Rome, Florence, Naples and the Amalfi Coast, studying the master painters of by centuries.[14] He exclaimed, "The Forum and the Vatican have spoken to me. Humanism wants to suffocate me."[sixteen] He responded to the colors of Italy, merely sadly noted, "that a long struggle lies in store for me in this field of colour."[17] For Klee, colour represented the optimism and nobility in art, and a promise for relief from the pessimistic nature he expressed in his black-and-white grotesques and satires.[17] Returning to Bern, he lived with his parents for several years, and took occasional art classes. By 1905, he was developing some experimental techniques, including drawing with a needle on a blackened pane of drinking glass, resulting in l-seven works including his Portrait of My Father (1906).[11] In the years 1903–05 he also completed a cycle of eleven zinc-plate etchings called Inventions, his start exhibited works, in which he illustrated several grotesque characters.[14] [eighteen] He commented, "though I'chiliad adequately satisfied with my etchings I tin't get on like this. I'm not a specialist."[xix] Klee was still dividing his time with music, playing the violin in an orchestra and writing concert and theater reviews.[20]

Matrimony and early years [edit]

Marriage [edit]

Bloom Myth (Blumenmythos) 1918, watercolor on pastel foundation on textile and newsprint mounted on board, Sprengel Museum, Hannover, Germany

Klee married Bavarian pianist Lily Stumpf in 1906 and they had 1 son named Felix Paul in the following year. They lived in a suburb of Munich, and while she gave pianoforte lessons and occasional performances, he kept firm and tended to his art work. His endeavor to be a mag illustrator failed.[20] Klee's art work progressed slowly for the adjacent v years, partly from having to divide his time with domestic matters, and partly as he tried to notice a new approach to his art. In 1910, he had his kickoff solo exhibition in Bern, which then travelled to three Swiss cities.

Affiliation to the "Blaue Reiter", 1911 [edit]

In January 1911, Alfred Kubin met Klee in Munich and encouraged him to illustrate Voltaire's Candide. His resultant drawings were published later in a 1920 version of the book edited past Kurt Wolff. Effectually this time, Klee's graphic piece of work increased. His early inclination towards the absurd and the sarcastic was well received past Kubin, who befriended Klee and became one of his first significant collectors.[21] Klee met, through Kubin, the art critic Wilhelm Hausenstein in 1911. Klee was a foundation member and director of the Munich artists' wedlock Sema that summer.[22] In autumn he made an associate with August Macke and Wassily Kandinsky, and in winter he joined the editorial squad of the almanac Der Blaue Reiter, founded by Franz Marc and Kandinsky. On meeting Kandinsky, Klee recorded, "I came to feel a deep trust in him. He is somebody, and has an exceptionally beautiful and lucid listen."[23] Other members included Macke, Gabriele Münter and Marianne von Werefkin. Klee became in a few months one of the almost of import and independent members of the Blaue Reiter, only he was not yet fully integrated.[24]

The release of the almanac was delayed for the benefit of an exhibition. The first Blaue Reiter exhibition took identify from 18 Dec 1911 to 1 January 1912 in the Moderne Galerie Heinrich Thannhauser in Munich. Klee did not attend information technology, but in the second exhibition, which occurred from 12 Feb to 18 March 1912 in the Galerie Goltz, 17 of his graphic works were shown. The name of this art exhibition was Schwarz-Weiß, every bit it just regarded graphic painting.[25] Initially planned to be released in 1911, the release date of the Der Blau Reiter almanac by Kandinsky and Marc was delayed in May 1912, including the reproduced ink drawing Steinhauer by Klee. At the aforementioned time, Kandinsky published his art history writing Über das Geistige in der Kunst.[26]

Participation in art exhibitions, 1912–1913 [edit]

The clan opened Klee'south listen to modern theories of color. His travels to Paris in 1912 also exposed him to the ferment of Cubism and the pioneering examples of "pure painting", an early term for abstract art. The apply of assuming color past Robert Delaunay and Maurice de Vlaminck likewise inspired him.[27] Rather than copy these artists, Klee began working out his own color experiments in pale watercolors and did some primitive landscapes, including In the Quarry (1913) and Houses most the Gravel Pit (1913), using blocks of color with limited overlap.[28] Klee acknowledged that "a long struggle lies in shop for me in this field of colour" in order to reach his "distant noble aim." Shortly, he discovered "the style which connects drawing and the realm of color."[17]

Trip to Tunis, 1914 [edit]

Klee's artistic quantum came in 1914 when he briefly visited Tunisia with August Macke and Louis Moilliet and was impressed past the quality of the light there. He wrote, "Color has taken possession of me; no longer practice I have to chase afterward it, I know that it has hold of me forever... Color and I are ane. I am a painter."[29] With that realization, faithfulness to nature faded in importance. Instead, Klee began to delve into the "cool romanticism of brainchild".[29] In gaining a 2nd artistic vocabulary, Klee added colour to his abilities in draftsmanship, and in many works combined them successfully, equally he did in i serial he chosen "operatic paintings".[30] [31] 1 of the most literal examples of this new synthesis is The Bavarian Don Giovanni (1919).[32]

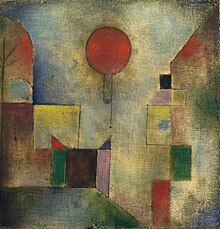

After returning home, Klee painted his first pure abstract, In the Fashion of Kairouan (1914), composed of colored rectangles and a few circles.[33] The colored rectangle became his basic building cake, what some scholars associate with a musical note, which Klee combined with other colored blocks to create a color harmony analogous to a musical limerick. His option of a particular color palette emulates a musical fundamental. Sometimes he uses complementary pairs of colors, and other times "dissonant" colors, again reflecting his connectedness with musicality.[34]

Armed services career [edit]

Paul Klee as a soldier, 1916

A few weeks later, World State of war I began. At first, Klee was somewhat detached from it, as he wrote ironically, "I have long had this war in me. That is why, inwardly, it is none of my concern."[35] Klee was conscripted as a Landsturmsoldat (soldier of the reserve forces in Prussia or Imperial Federal republic of germany) on 5 March 1916. The deaths of his friends Baronial Macke and Franz Marc in battle began to affect him. Venting his distress, he created several pen and ink lithographs on war themes including Decease for the Idea (1915).[36] After finishing the military training course, which began on 11 March 1916, he was committed every bit a soldier backside the forepart. Klee moved on 20 Baronial to the aircraft maintenance company[b] in Oberschleissheim, executing skilled manual work, such as restoring aircraft camouflage, and accompanying aircraft transports. On 17 January 1917, he was transferred to the Imperial Bavarian flight school in Gersthofen (which 54 years later became the USASA Field Station Augsburg) to work every bit a clerk for the treasurer until the end of the state of war. This allowed him to stay in a small room outside of the barrack cake and proceed painting.[37] [38]

He continued to paint during the entire war and managed to exhibit in several shows. By 1917, Klee'southward work was selling well and art critics acclaimed him every bit the best of the new German artists.[39] His Ab ovo (1917) is particularly noteworthy for its sophisticated technique. It employs watercolor on gauze and newspaper with a chalk basis, which produces a rich texture of triangular, circular, and crescent patterns.[29] Demonstrating his range of exploration, mixing color and line, his Warning of the Ships (1918) is a colored cartoon filled with symbolic images on a field of suppressed color.[40]

Mature career [edit]

In 1919, Klee applied for a teaching post at the University of Art in Stuttgart.[41] This attempt failed merely he had a major success in securing a three-year contract (with a minimum annual income) with dealer Hans Goltz, whose influential gallery gave Klee major exposure, and some commercial success. A retrospective of over 300 works in 1920 was likewise notable.[42]

Klee taught at the Bauhaus from January 1921 to April 1931.[43] He was a "Grade" main in the bookbinding, stained glass, and landscape painting workshops and was provided with two studios.[44] In 1922, Kandinsky joined the staff and resumed his friendship with Klee. Later that year the first Bauhaus exhibition and festival was held, for which Klee created several of the advertising materials.[45] Klee welcomed the many conflicting theories and opinions within the Bauhaus: "I besides approve of these forces competing one with the other if the upshot is achievement."[46]

Tropical Gardening, 1923 watercolor and oil transfer drawing on paper, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

Klee was too a member of Die Blaue Vier (The Blue Four), with Kandinsky, Lyonel Feininger, and Alexej von Jawlensky; formed in 1923, they lectured and exhibited together in the United states of america in 1925. That aforementioned yr, Klee had his first exhibits in Paris, and he became a hit with the French Surrealists.[47] Klee visited Arab republic of egypt in 1928, which impressed him less than Tunisia. In 1929, the outset major monograph on Klee's piece of work was published, written past Will Grohmann.[48]

Nocturnal Festivity, 1921, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

Klee as well taught at the Düsseldorf Academy from 1931 to 1933, and was singled out by a Nazi newspaper, "Then that groovy fellow Klee comes onto the scene, already famed as a Bauhaus teacher in Dessau. He tells everyone he's a thoroughbred Arab, but he's a typical Galician Jew."[49] His home was searched past the Gestapo and he was fired from his job.[iii] [50] His self-portrait Struck from the Listing (1933) commemorates the deplorable occasion.[49] In 1933–34, Klee had shows in London and Paris, and finally met Pablo Picasso, whom he greatly admired.[51] The Klee family emigrated to Switzerland in late 1933.[51]

Klee was at the meridian of his creative output. His Advertizement Parnassum (1932) is considered his masterpiece and the best example of his pointillist fashion; it is also one of his largest, virtually finely worked paintings.[52] [53] He produced well-nigh 500 works in 1933 during his last year in Germany.[54] Yet, in 1933, Klee began experiencing the symptoms of what was diagnosed as scleroderma after his death. The progression of his fatal illness, which made swallowing very difficult, can be followed through the art he created in his last years. His output in 1936 was only 25 pictures. In the later 1930s, his wellness recovered somewhat and he was encouraged past a visit from Kandinsky and Picasso.[55] Klee's simpler and larger designs enabled him to proceed up his output in his last years, and in 1939 he created over ane,200 works, a career loftier for one yr.[56] He used heavier lines and mainly geometric forms with fewer but larger blocks of colour. His varied color palettes, some with bright colors and others somber, perhaps reflected his alternating moods of optimism and pessimism.[57] Back in Germany in 1937, seventeen of Klee's pictures were included in an exhibition of "Degenerate art" and 102 of his works in public collections were seized by the Nazis.[58]

Death [edit]

Klee'southward grave in Schosshalden cemetery

In 1935, two years later moving to Switzerland and working in a very confined state of affairs, Klee adult scleroderma, an autoimmune disease resulting in hardening of connective tissue.[59]

He endured pain that seems to be reflected in his last works of art.[ citation needed ] In his last months he created fifty drawings of angels.[59] One of his last paintings, Death and Fire, features a skull in the center with the German discussion for death, "Tod", appearing in the face. He died in Muralto, Locarno, Switzerland, on 29 June 1940 without having obtained Swiss citizenship, despite his birth in that state.[sixty] [61] His fine art work was considered likewise revolutionary, fifty-fifty degenerate, by the Swiss authorities, but eventually they accepted his asking six days subsequently his death.[62] His legacy comprised nearly 9,000 works of art.[17] The words on his tombstone, Klee's credo, placed there by his son Felix, say, "I cannot be grasped in the here and at present, for my dwelling place is as much among the dead as the yet unborn. Slightly closer to the centre of creation than usual, but however non close plenty."[63] He was buried at Schosshaldenfriedhof, Bern, Switzerland.

Style and methods [edit]

Tale à la Hoffmann (1921), watercolor, ink, and pencil on paper. 31.one × 24.1 cm. In the drove of the Metropolitan Museum of Fine art, New York

Klee has been variously associated with Expressionism, Cubism, Futurism, Surrealism, and Abstraction, but his pictures are difficult to classify. He generally worked in isolation from his peers, and interpreted new art trends in his ain way. He was inventive in his methods and technique. Klee worked in many different media—oil paint, watercolor, ink, pastel, etching, and others. He often combined them into ane work. He used canvas, burlap, muslin, linen, gauze, cardboard, metallic foils, fabric, wallpaper, and newsprint.[64] Klee employed spray paint, knife application, stamping, glazing, and impasto, and mixed media such as oil with watercolor, watercolor with pen and India ink, and oil with tempera.[65]

He was a natural draftsman, and through long experimentation developed a mastery of color and tonality. Many of his works combine these skills. He uses a great variety of color palettes from well-nigh monochromatic to highly polychromatic. His works frequently have a frail childlike quality to them and are usually on a small scale. He oftentimes used geometric forms and grid format compositions too as letters and numbers, ofttimes combined with playful figures of animals and people. Some works were completely abstract. Many of his works and their titles reverberate his dry humor and varying moods; some express political convictions. They frequently allude to poetry, music and dreams and sometimes include words or musical notation. The later works are distinguished past spidery hieroglyph-like symbols. Rainer Maria Rilke wrote about Klee in 1921, "Even if y'all hadn't told me he plays the violin, I would take guessed that on many occasions his drawings were transcriptions of music."[13]

Pamela Kort observed: "Klee's 1933 drawings present their beholder with an unparalleled opportunity to glimpse a central attribute of his aesthetics that has remained largely unappreciated: his lifelong concern with the possibilities of parody and wit. Herein lies their real significance, particularly for an audience unaware that Klee's art has political dimensions."[66]

Among the few plastic works are hand puppets fabricated betwixt 1916 and 1925, for his son Felix. The artist neither counted them every bit a component of his oeuvre, nor did he list them in his catalogue raisonné. Thirty of the preserved puppets are stored at the Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern.[67]

Works [edit]

Early on works [edit]

Some of Klee's early preserved children's drawings, which his grandmother encouraged, were listed on his catalogue raisonné. A total of 19 etchings were produced during the Bern years; x of these were made between 1903 and 1905 in the cycle "Inventionen" (Inventions),[68] which were presented in June 1906 at the "Internationale Kunstausstellung des Vereins bildender Künstler Münchens 'Secession'" (International Art Exhibition of the Clan for Graphic Arts, Munich, Secession), his first appearance as a painter in the public.[69] Klee had removed the third Invention, Pessimistische Allegorie des Gebirges (Pessimistic Allegory of the Mountain), in February 1906 from his cycle.[70] The satirical etchings, for example Jungfrau im Baum/Jungfrau (träumend) (Virgin on the tree/Virgin (dreaming)) from 1903 and Greiser Phoenix (Aged Phoenix) from 1905, were classified by Klee equally "surrealistic outposts". Jungfrau im Baum ties on the motive Le cattive madri (1894) by Giovanni Segantini. The flick was influenced by grotesque lyric poetries of Alfred Jarry, Max Jacob and Christian Morgenstern.[71] It features a cultural cynicism, which can be institute at the turn of the 20th century in works by Symbolists. The Invention Nr. 6, the 1903 etching Zwei Männer, einander in höherer Stellung vermutend (Ii Men, Supposing the Other to exist in a Higher Position), depicts two naked men, presumably emperor Wilhelm 2 and Franz Joseph I of Republic of austria, recognizable by their hairstyle and beards. Every bit their apparel and insignia were bereft, "both of them have no inkling if their conventional salute […] is in order or not. As they assume that their analogue could have been higher rated", they bow and scrape.[72]

-

Dame mit Sonnenschirm, 1883–1885, pencil on newspaper on paper-thin, Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern

-

Sixth Invention: Zwei Männer, einander in höherer Stellung vermutend, begegnen sich, 1903, etching, Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern

Klee began to introduce a new technique in 1905: scratching on a blackened glass console with a needle. In that manner he created about 57 Verre églomisé pictures, amongst those the 1905 Gartenszene (Scene on a Garden) and the 1906 Porträt des Vaters (Portrait of a Father), with which he tried to combine painting and scratching.[73] Klee'due south solitary early on work concluded in 1911, the year he met and was inspired by the graphic artist Alfred Kubin, and became associated with the artists of the Blaue Reiter.[74]

Mystical-abstruse catamenia, 1914–1919 [edit]

During his twelve-twenty-four hours educational trip to Tunis in April 1914 Klee produced with Macke and Moilliet watercolor paintings, which implement the strong light and color stimulus of the Due north African countryside in the fashion of Paul Cézanne and Robert Delaunays' cubistic form concepts. The aim was not to imitate nature, just to create compositions analogous to nature'southward formative principle, as in the works In den Häusern von Saint-Germain (In the Houses of Saint-Germain) and Straßencafé (Streetcafé). Klee conveyed the scenery in a grid, so that it dissolves into colored harmony. He besides created abstract works in that period such as Abstract and Farbige Kreise durch Farbbänder verbunden (Colored Circles Tied Through Inked Ribbons).[75] He never abandoned the object; a permanent segregation never took place. It took over ten years that Klee worked on experiments and assay of the colour, resulting to an independent bogus work, whereby his design ideas were based on the colorful oriental world.

-

Fenster und Palmen, 1914, watercolor on grounding on paper on cardboard, Kunsthaus Zürich, Zurich

-

In den Häusern von St. Germain, 1914, watercolor on paper on cardboard, Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern

-

Föhn im Marc'schen Garten, 1915, watercolor on paper on paper-thin, Lenbachhaus, Munich

Föhn im Marc'schen Garten (Foehn at Marc'south Garden) was made later on the Turin trip. Information technology indicates the relations between color and the stimulus of Macke and Delaunay. Although elements of the garden are conspicuously visible, a further steering towards abstraction is noticeable. In his diary Klee wrote the following note at that fourth dimension:

In the large molding pit are lying ruins, on which one partially hangs. They provide the material for the abstraction. […] The terrible the world, the abstract the art, while a happy earth produces secularistic fine art.[76]

Nether the impression of his military machine service he created the painting Trauerblumen (Velvetbells) in 1917, which, with its graphical signs, vegetal and phantastic shapes, is a forerunner of his future works, harmonically combining graphic, colour and object. For the first time birds announced in the pictures, such as in Blumenmythos (Flower Myth) from 1918, mirroring the flight and falling planes he saw in Gersthofen, and the photographed airplane crashes.

In the 1918 watercolor painting Einst dem Grau der Nacht enttaucht, a compositional implemented poem, possibly written past Klee, he incorporated letters in small, in terms of color separated squares, cutting off the first poesy from the 2nd one with silver paper. At the acme of the cardboard, which carries the motion picture, the verses are inscribed in manuscript grade. Hither, Klee did not lean on Delaunay's colors, but on Marc's, although the moving-picture show content of both painters does not correspond with each other. Herwarth Walden, Klee's art dealer, saw in them a "Wachablösung" (irresolute of the guard) of his art.[77] Since 1919 he often used oil colors, with which he combined watercolors and colored pencil. The Villa R (Kunstmuseum Basel) from 1919 unites visible realities such as sun, moon, mountains, copse and architectures, likewise as surreal pledges and sentiment readings.[78]

Works in the Bauhaus period and in Düsseldorf [edit]

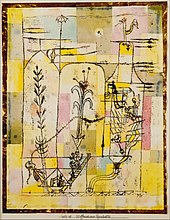

His works during this time include Camel (in rhythmic landscape with trees) besides as other paintings with abstract graphical elements such as betroffener Ort (Affected Place) (1922). From that period he created Die Zwitscher-Maschine (The Twittering Machine), which was later removed from the National Gallery. After being named defamatory in the Munich exhibition "Entartete Kunst", the painting was after bought past the Buchholz Gallery, New York, and then transferred in 1939 to the Museum of Modern Fine art. The "twittering" in the championship refers to the open-beaked birds, while the "machine" is illustrated by the crank.[79]

In Engelshut, 1931, watercolor and colored inks on paper, mounted on newspaper, Guggenheim Museum

The watercolor painting appears at a first glance kittenish, but it allows more interpretations. The picture tin can be interpreted every bit a critic past Klee, who shows through denaturation of the birds, that the world technization heist the creatures' self-determination.[80]

Other examples from that flow are der Goldfisch (The Goldfish) from 1925, Katze und Vogel (True cat and Bird), from 1928, and Hauptweg und Nebenwege (Main Route and Byways) from 1929. Through variations of the canvas ground and his combined painting techniques Klee created new colour effects and picture show impressions.

From 1916 to 1925, Klee created fifty paw puppets for his son Felix. The puppets are not mentioned in the Bauhaus catalog of works, since they were intended as individual toys from the offset.[81] Nevertheless, they are an impressive example of Klee'southward imagery. He not simply dealt with puppet shows privately, just also in his artistic piece of work at the Bauhaus.[82]

In 1931, Klee transferred to Düsseldorf to teach at the Akademie; the Nazis shut down the Bauhaus before long after.[83] During this time, Klee illustrated a series of guardian angels. Amid these figurations is "In Engelshut" (In the Angel's Care). Its overlaying technique evinces the polyphonic character of his cartoon method between 1920 and 1932.[84]

The 1932 painting Ad Parnassum was also created in the Düsseldorf period. 100 cm × 126 cm (39 in × fifty in) This is one of his largest paintings, every bit he usually worked with small formats. In this mosaic-like work in the way of pointillism he combined dissimilar techniques and compositional principles. Influenced by his trip to Egypt from 1928 to 1929, Klee congenital a color field from individually stamped dots, surrounded by similarly stamped lines, which results in a pyramid. In a higher place the roof of the "Parnassus" there is a sun. The championship identifies the picture every bit the home of Apollo and the Muses.[85] During his 1929 travels through Egypt, Klee developed a sense of connectedness to the state, described by art historian Olivier Berggruen as a mystical feeling: "In the desert, the sun's intense rays seemed to envelop all living things, and at night, the motion of the stars felt fifty-fifty more palpable. In the compages of the aboriginal funerary moments Klee discovered a sense of proportion and measure in which human being beings appeared to establish a convincing human relationship with the immensity of the landscape; furthermore, he was drawn to the esoteric numerology that governed the way in which these monuments had been built."[86] In 1933, his last year in Germany, he created a range of paintings and drawings; the catalogue raisonné comprised 482 works. The self-portrait in the same year—with the programmatic title von der Liste gestrichen (removed from the listing)—provides information about his feeling afterward losing his professorship. The abstruse portrait was painted in dark colors and shows closed optics and compressed lips, while on the back of his caput there is a large "X", symbolizing that his art was no longer valued in Germany.[87]

-

Fright of a Girl, 1922, Watercolor, India ink and oil transfer drawing on newspaper, with Bharat ink on paper mount, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

-

Puppet without championship (self - portrait), 1922

Last works in Switzerland [edit]

In this period Klee mainly worked on large-sized pictures. Subsequently the onset of illness, there were about 25 works in the 1936 catalogue, simply his productivity increased in 1937 to 264 pictures, 1938 to 489, and 1939—his most productive yr—to 1254. They dealt with clashing themes, expressing his personal fate, the political situation and his wit. Examples are the watercolor painting Musiker (musician), a stick-human face up with partially serious, partially grinning mouth; and the Revolution des Viadukts (Revolution of the Viadukt), an anti-fascist art. In Viadukt (1937) the bridge arches split from the bank as they refuse to be linked to a concatenation and are therefore rioting.[88] Since 1938, Klee worked more intensively with hieroglyphic-similar elements. The painting Insula dulcamara from the same year, which is one of his largest (88 cm × 176 cm (35 in × 69 in)), shows a white face in the heart of the elements, symbolizing death with its black-circled heart sockets. Bitterness and sorrow are not rare in much of his works during this time.

-

Zeichen in Gelb, 1937, pastel on cotton on colored paste on jute on stretcher frame, Fondation Beyeler, Riehen nearly Basel

-

Nach der Überschwemmung, 1936, wallpaper gum and watercolors on Ingres paper on paper-thin

-

Revolution des Viadukts, 1937, oil on oil grounding on cotton wool on stretcher frame, Hamburger Kunsthalle

-

Die Vase, 1938, oil on jute, Fondation Beyeler, Riehen almost Basel

-

Ohne Titel (Letztes Stillleben), 1940, oil on canvass on stretcher frame, Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern

-

Tod und Feuer (Expiry and Fire), 1940, oil on distemper on jute, Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern

Klee created in 1940 a flick which strongly differs from the previous works, leaving it unsigned on the scaffold. The insufficiently realistic yet life, Ohne Titel, later named as Der Todesengel (Affections of Expiry), depicts flowers, a greenish pot, sculpture and an affections. The moon on black basis is separated from these groups. During his 60th birthday Klee was photographed in front end of this picture.[89]

Reception and legacy [edit]

| External video | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

Contemporary view [edit]

Was fehlt ihm? (What Is He Missing?), 1930, postage stamp drawing in ink, Ingres paper on paper-thin, Fondation Beyeler, Riehen almost Basel

Art does non reproduce the visible; rather, information technology makes visible.

"Klee's act is very prestigious. In a minimum of ane line he can reveal his wisdom. He is everything; profound, gentle and many more of the good things, and this considering: he is innovative", wrote Oskar Schlemmer, Klee's hereafter artist colleague at the Bauhaus, in his September 1916 diary.[90]

Novelist and Klee'south friend Wilhelm Hausenstein wrote in his work Über Expressionismus in der Malerei (On Expressionism in Painting), "Maybe Klee's attitude is in full general understandable for musical people—how Klee is 1 of the about delightsome violinist playing Bach and Händel, who ever walked on earth. […] For Klee, the German classic painter of the Cubism, the world music became his companion, possibly even a part of his art; the composition, written in notes, seems to be not dissimilar."[91]

When Klee visited the Paris surrealism exhibition in 1925, Max Ernst was impressed past his piece of work. His partially morbid motifs appealed to the surrealists. André Breton helped to develop the surrealism and renamed Klee'south 1912 painting Zimmerperspektive mit Einwohnern (Room Perspective with People) to chambre spirit in a catalogue. Critic René Crevel called the artist a "dreamer" who "releases a swarm of small lyrical louses from mysterious abysses." Paul Klee'south confidante Will Grohmann argued in the Cahiers d'art that he "stands definitely well solid on his feet. He is by no ways a dreamer; he is a modern person, who teaches as a professor at the Bauhaus." Whereupon Breton, equally Joan Miró remembers, was disquisitional of Klee: "Masson and I have both discovered Paul Klee. Paul Éluard and Crevel are besides interested in Klee, and they have even visited him. Only Breton despises him."[92]

The art of mentally ill people inspired Klee as well every bit Kandinsky and Max Ernst, after Hans Prinzhorns book Bildnerei der Geisteskranken (Artistry of the Mentally Ill) was published in 1922. In 1937, some papers from Prinzhorn'due south album were presented at the National Socialist propaganda exhibition "Entartete Kunst" in Munich, with the purpose of defaming the works of Kirchner, Klee, Nolde and other artists by likening them to the works of the insane.[93]

In 1949 Marcel Duchamp commented on Paul Klee: "The first reaction in front of a Klee painting is the very pleasant discovery, what everyone of the states could or could take done, to try drawing like in our babyhood. Most of his compositions show at the first glance a plain, naive expression, found in children'due south drawings. […] At a second analyse one tin can discover a technique, which takes as a basis a large maturity in thinking. A deep understanding of dealing with watercolors to paint a personal method in oil, structured in decorative shapes, let Klee stand out in the gimmicky art and make him incomparable. On the other side, his experiment was adopted in the final 30 years by many other artists equally a basis for newer creations in the most different areas in painting. His extreme productivity never shows evidence of repetition, equally is normally the case. He had so much to say, that a Klee never became another Klee."[94]

I of Klee'south paintings, Angelus Novus, was the object of an interpretative text by German language philosopher and literary critic Walter Benjamin, who purchased the painting in 1921. In his "Theses on the Philosophy of History" Benjamin suggests that the angel depicted in the painting might exist seen as representing the angel of history.

Another aspect of his legacy, and 1 demonstrating his multi-faceted presence in the modern artistic imagination, is his appeal for those interested in the history of the algorithm as exemplified by Homage to Paul Klee by computer fine art pioneer Frieder Nake.[95]

Musical interpretations [edit]

Different his taste for audacious modern experiment in painting, Klee, though musically talented, was attracted to older traditions of music; he appreciated neither composers of the late 19th century, such as Wagner, Bruckner and Mahler, nor gimmicky music. Bach and Mozart were for him the greatest composers; he most enjoyed playing the works past the latter.[96]

Klee's work has influenced composers such equally Argentinian Roberto García Morillo in 1943, with Tres pinturas de Paul Klee. Others include the American composer David Diamond in 1958, with the four-part Opus Welt von Paul Klee (World of Paul Klee). Gunther Schuller equanimous Seven Studies on Themes of Paul Klee in the years 1959/60, consisting of Antique Harmonies, Abstract Trio, Little Bluish Devil, Twittering Machine, Arab Hamlet, An Eerie Moment, and Pastorale. The Spanish composer Benet Casablancas wrote Alter Klang, Impromptu for Orchestra subsequently Klee (2006);[97] [98] Casablancas is writer also of the Retablo on texts by Paul Klee, Cantata da Camera for Soprano, Mezzo and Piano (2007).[99] [100] In 1950, Giselher Klebe performed his orchestral work Die Zwitschermaschine with the subtitle Metamorphosen über das Bild von Paul Klee at the Donaueschinger Musiktage.[101] 8 Pieces on Paul Klee is the title of the debut anthology by the Ensemble Sortisatio, recorded February and March 2002 in Leipzig and August 2002 in Lucerne, Switzerland. The composition "Wie der Klee vierblättrig wurde" (How the clover became iv-leaved) was inspired past the watercolor painting Hat Kopf, Paw, Fuss und Herz (1930), Angelus Novus and Hauptweg und Nebenwege.

In 1968, a jazz group called The National Gallery featuring composer Chuck Mangione released the anthology Performing Musical Interpretations of the Paintings of Paul Klee.[102] In 1995 the Greek experimental filmmaker, Kostas Sfikas, created a motion picture based entirely on Paul Klee's paintings. The film is entitled "Paul Klee's Prophetic Bird of Sorrows", and draws its title from Klee'due south Landscape with Yellowish Birds. It was made using portions and cutouts from Paul Klee's paintings.

Additional musical interpretations [edit]

- Sándor Veress: Hommage à Paul Klee (1951), phantasy for two pianos and strings

- Peter Maxwell Davies: 5 Klee-Pictures (1962), orchestral

- Harrison Birtwistle: Carmen Arcadiae Mechanicae Perpetuum (The Perpetual Vocal of Mechanical Arcadia) (1977), for orchestra

- Edison Denisov: Drei Bilder von Paul Klee (Three Pictures of Paul Klee) (1985), for 6 players (Diana im Herbstwind − Senecio – Kind auf der Freitreppe)

- Tōru Takemitsu: All in Twilight (1987), for guitar

- John Woolrich: The kingdom of dreams (1989), for oboe and pianoforte ('Mural with Xanthous Birds', 'The Bavarian Don Giovanni', 'Tale à la Hoffmann', 'Fish Magic')

- Leo Brouwer: Sonata (1990), for guitar[103]

- Walter Steffens: Vier Aquarelle nach Paul Klee (Four Watercolor Pictures to Paul Klee) (1991), op. 63, for recorder(southward)

- Tan Dun: Expiry and Fire (1992), Dialogue with Paul Klee, orchestral

- Judith Weir: Heroic Strokes of the Bow (1992), for orchestra

- Jean-Luc Darbellay: Ein Garten für Orpheus (A Garden for Orpheus) (1996), for six instruments

- Michael Denhoff: Haupt- und Nebenwege (Chief and Sideways) (1998), for strings and piano

- Iris Szeghy: Ad parnassum (2005), for strings

- Patrick van Deurzen: Half dozen: a line is a dot that went for a walk (2006), for Flugelhorn, DoubleBass & Percussion

- Jim McNeely: Paul Klee (2007), Jazz album written for the Swiss Jazz Orchestra equanimous of 8 pieces

- Jason Wright Wingate: Symphony No. two: Kleetüden; Variationen für Orchester nach Paul Klee (Variations for Orchestra subsequently Paul Klee) (2009), for orchestra in 27 movements

- Sakanaction: "Klee" (2010), from the album Kikuuiki; a vocal envisioned as a dialogue with Klee'due south paintings.[104]

- Ludger Stühlmeyer: Super flumina Babylonis [An den Wassern zu Boom-boom]. (2019), fantasia for organ (Introduzione, Scontro, Elegie, Appassionato) on an aquarelle by Paul Klee.

Architectural honors [edit]

Since 1995, the "Paul Klee-Archiv" (Paul Klee annal) of the University of Jena houses an extensive drove of works past Klee. It is located within the fine art history department, established by Franz-Joachim Verspohl. Information technology encompasses the individual library of book collector Rolf Sauerwein which contains nearly 700 works from 30 years equanimous of monographs about Klee, exhibition catalogues, extensive secondary literature as well as originally illustrated problems, a postcard and a signed photography portrait of Klee.[105] [106]

Builder Renzo Pianoforte constructed the Zentrum Paul Klee in June 2005. Located in Bern, the museum exhibits about 150 (of 4000 Klee works overall) in a six-calendar month rotation, as it is incommunicable to evidence all of his works at once. Furthermore, his pictures crave remainder periods; they comprise relatively photosensitive colors, inks and papers, which may bleach, change, plough brown and become breakable if exposed to light for as well long.[107] The San Francisco Museum of Modernistic Fine art has a comprehensive Klee drove, donated by Carl Djerassi. Other exhibitions include the Sammlung Rosengart in Luzern, the Albertina in Wien and the Berggruen Museum in Berlin. Schools in Gersthofen, Lübeck; Klein-Winternheim, Overath; his place of nascency Münchenbuchsee and Düsseldorf acquit his name.

Tribute [edit]

In 2018, a Google Putter was created to celebrate his 139th birthday.[108]

Publications [edit]

- Jardi, Enric (1991). Paul Klee, Rizzoli Intl Pubns, ISBN 0-8478-1343-6

- Kagan, Andrew (1993). Paul Klee at the Guggenheim Museum (exhibition catalogue) [1] Introduction past Lisa Dennison, essay by Andrew Kagan. 208 pages. English and Spanish editions. 1993, ISBN 978-0-89207-106-7

- Cappelletti, Paolo (2003). L'inafferrabile visione. Pittura e scrittura in Paul Klee (in Italian). Milan: Jaca Volume. ISBN 88-16-40611-9

- Partsch, Susanna (2007). Klee (reissue) (in German language). Cologne: Benedikt Taschen. ISBN978-3-8228-6361-nine.

- Rudloff, Diether (1982). Unvollendete Schöpfung: Künstler im zwanzigsten Jahrhundert (in German). ISBN978-3-87838-368-0.

- Baumgartner, Michael; Klingsöhr-Leroy, Cathrin; Schneider, Katja (2010). Franz Marc, Paul Klee: Dialog in Bildern (in German) (1st ed.). Wädenswil: Nimbus Kunst und Bücher. ISBN978-3-907142-50-9.

- Giedion-Welcker, Carola (1967). Klee (in High german). Reinbek: Rowohlt. ISBN978-3-499-50052-7.

- Glaesemer, Jürgen; Kersten, Wolfgang; Traffelet, Ursula (1996). Paul Klee: Leben und Werk (in High german). Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz. ISBN978-3-7757-0241-6.

- Rümelin, Christian (2004). Paul Klee: Leben und Werk. Munich: C.H. Beck. ISBN3-406-52190-8.

- Lista, Marcella (2011). Paul Klee, 1879-1940 : polyphonies. Arles: Actes Sud. ISBN 978-2330000530

Books, essays and lectures by Paul Klee [edit]

- 1922 Beiträge zur bildnerischen Formlehre ('Contributions to a pictorial theory of form', part of his 1921–22 lectures at the Bauhaus)

- 1923 Wege des Naturstudiums ('Ways of Studying Nature'), 4 pages. Published in the catalogue for the Erste Bauhaus Ausstellung (First Bauhaus Exhibition) in Summer 1923. Also published in Paul Klee Notebooks vol i.

- 1924 Über moderne Kunst ('On Modern Art'), lecture held at Paul Klee's exhibition at the Kunstverein in Jena on 26 January 1924

- 1924 Pädagogisches Skizzenbuch ('Pedagogical Sketchbook')

- 1949 Documente und Bilder aus den Jahren 1896–1930, ('Documents and images from the years 1896–1930'), Berne, Benteli

- 1956 Graphik, ('Graphics'), Berne, Klipstein & Kornfeld

- 1956 Schriften zur Class und Gestaltungslehre ('Writings on class and blueprint theory') edited by Jürg Spiller (English edition: 'Paul Klee Notebooks')

- 1956 Band I: Das bildnerische Denken., ('Book I: the creative thinking'). 572 pages review. (English translation from German by Ralph Manheim: 'The thinking eye')

- 1964 Band 2: Unendliche Naturgeschichte ('Volume 2: Infinite Natural History') (English translation from German by Heinz Norden: 'The Nature of Nature')

- 1964 The Diaries of Paul Klee 1898–1918 ed. Felix Klee Berkeley, University of California

- 1976 Schriften, Rezensionen und Aufsätze edited by Ch. Geelhaar, Köln,

- 1960 Gedichte, poems, edited past Felix Klee

- 1962 Some poems by Paul Klee ed Anselm Hollo. London

Meet also [edit]

- Colour theory

- Watercolors

- Expressionism

- Der Blaue Reiter

Notes and references [edit]

Notes [edit]

- a Paul Klee's father was a German language citizen; his mother was Swiss. Swiss law determined citizenship along paternal lines, and thus Paul inherited his father's German citizenship. He served in the German ground forces during World War I. Klee grew up in Berne, Switzerland, and returned there often, even before his last emigration from Frg in 1933. He died earlier his application for Swiss citizenship was processed.[109] [110]

- b High german: Werftkompanie, lit. 'shipyard company'.

References [edit]

- ^ Disegno e progettazione By Marcello Petrignani p. 17

- ^ Guilo Carlo Argan "Preface", Paul Klee, The Thinking Center, (ed. Jürg Spiller), Lund Humphries, London, 1961, p. 13.

- ^ a b The private Klee: Works by Paul Klee from the Bürgi Collection Archived ix October 2009 at the Wayback Machine Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, 12 August – 20 October 2000

- ^ Gualtieri Di San Lazzaro, Klee, Praeger, New York, 1957, p. 16

- ^ Rudloff, p. 65

- ^ Baumgartner, p. 199

- ^ Giedion-Welcker, pp. 10–11

- ^ a b Partsch, p. 9

- ^ Kagan p. 54

- ^ Partsch, p. seven

- ^ a b Partsch, p. 10

- ^ a b Kagan, p. 22

- ^ a b Jardi, p. viii

- ^ a b c Partsch, p. 11

- ^ Olga'due south Gallery Paul Klee

- ^ Jardi, p. 9

- ^ a b c d Kagan, p. 23

- ^ "Invention" Paul Klee at the Museum of Gimmicky Art San Francisco ARTinvestment.RU – 18 April 2009

- ^ Jardi, p. 10

- ^ a b Partsch, p. 12

- ^ Beate Ofczarek, Stefan Frey: Chronologie einer Freundschaft. Michael Baumgartner, Cathrin Klingsöhr-Leroy, Katja Schneider, p. 207

- ^ Thomas Kain, Mona Meister, Franz-Joachim Verspohl, Jena 1999, p. ninety

- ^ Jardi, p. 12

- ^ Göttler: Der Blaue Reiter, p. 118

- ^ Dietmar Elger, Expressionismus. 1988, p. 141, ISBN iii-8228-0093-7

- ^ Catalogue raisonné, volume i, 1998, p. 512; Thomas Kain, Mona Meister, Franz-Joachim Verspohl; Paul Klee in Jena 1924. Der Vortrag. Minerva. Writings from Jena to Art History, volume 10, fine art history seminar, Jenoptik AG, impress firm Gera, Jena 1999, p. 92

- ^ Partsch, p. eighteen

- ^ Jardi, plate 7, 9

- ^ a b c Partsch, p. 20

- ^ Partsch, pp. 24–25

- ^ Kagan, p. 33

- ^ Kagan, p. 35

- ^ Partsch, p. 27

- ^ Kagan, pp. 27, 29.

- ^ Partsch, p. 31

- ^ Reproduced aslope Gerg Traki'south poem in Zeit-Echo 1915.A contrary ekphrasis.

- ^ Beate Ofczarek, Stefan Frey: Chronologie einer Freundschaft, pp. 214 et seqq

- ^ Partsch, p. 35

- ^ Partsch, p. 36

- ^ Partsch, p. 40

- ^ Anger, Jenny. Paul Klee and the Decorative in Modern Fine art, Cambridge University Press 2004 pp. 120–122

- ^ Partsch, p. 44

- ^ Geelhaar, Christian (1972). Paul Klee und das Bauhaus. DuMont Schauberg, Köln, p. 9

- ^ Jardi, p. 17

- ^ Jardi, p. 18

- ^ Partsch, p. 48

- ^ Jardi, pp. 18–19

- ^ Jardi, p. xx

- ^ a b Partsch, p. 73

- ^ Partsch, p. 55

- ^ a b Jardi, p. 23

- ^ Partsch, p. 64

- ^ Kagan, p. 42

- ^ Partsch, p. 74

- ^ Jardi, p. 25

- ^ Partsch, p. 76

- ^ Partsch, pp. 77–80

- ^ Partsch, p. 94

- ^ a b Angelika Obert (20 September 2015). "Paul Klee und das innere Schauen". rundfunk.evangelisch.de (in German). Retrieved 30 March 2021 – via Deutschlandfunk Kultur.

- ^ Suter, Hans (eighteen April 2014). "Case Report on the Illness of Paul Klee (1879–1940)". Instance Reports in Dermatology. vi (one): 108–113. doi:x.1159/000360963. PMC4025051. PMID 24876831.

- ^ swissinfo.ch, S. W. I.; Corporation, a branch of the Swiss Broadcasting. "Ein Berner, aber kein Schweizer Künstler". SWI swissinfo.ch (in German language). Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ Partsch, p. 80

- ^ Partsch, p. 84

- ^ Kagan, p. 26

- ^ Partsch, pp. 58–threescore

- ^ Paul Klee 1933 Archived thirteen May 2008 at the Wayback Car at www.culturekiosque.com

- ^ Daniel Kupper: Paul Klee. p. 81

- ^ Christian Rümelin: Paul Klee. Leben und Werk, München 2004, pp. 12 et seq. online

- ^ Beate Ofczarek, Stefan Frey: Chronologie einer Freundschaft, p. 203

- ^ Gregor Wedekind: Paul Klee: Inventionen. Reimer, Berlin 1996, p. 62

- ^ Giedion-Welcker: Klee, pp. 23 et seqq

- ^ Christian Rümelin: Paul Klee. Leben und Werk, Munichn 2004, p. 15

- ^ Giedion-Welcker, Klee, pp. 22–25

- ^ Temkin, Ann . "Klee, Paul." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Web.

- ^ "Paul Klee". Meisterwerke der Kunst, Isis Verlag. Archived from the original on 9 January 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2008.

- ^ Göttler: Der Blaue Reiter. pp. 118 et seq

- ^ Partsch: Klee, p. 41

- ^ "Kunst öffnet Augen". augen.de. Archived from the original on ix January 2009. Retrieved 26 Oct 2008.

- ^ The Twittering-Automobile, moma.org, retrieved on 10 Jan 2011.

- ^ Siglind Bruhn: Das tönende Museum, Gorz Verlag 2004, pp. 34 et seq

- ^ Ingeborg Ruthe (30 September 2008). "Paul Klee hinterließ kunstvolle Handpuppen. Berliner Spieler bringen sie auf die Bühne in einem Stück über das Malerleben". Berliner-zeitung.de. DuMont.side by side GmbH & Co. KG.

- ^ "Über den Klee oder Der Knochen in meinem Kopf". Tabula Rasa Magazin – Zeitung für Gesellschaft und Kultur. Dr. Dr. Stefan Groß, M.A. 28 April 2009.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 Apr 2015. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy every bit title (link) - ^ Andrew Kagan, Paul Klee at the Guggenheim Museum, New York: Guggenheim Museum Library, 2003, 41.

- ^ Partsch: Klee, p. 67

- ^ Berggruen, "Paul Klee – In Search of Natural Signs" in The Writing of Art (London: Pushkin Press, 2011), 63.

- ^ Partsch: Klee, p. 75

- ^ Partsch: Klee, p. 92

- ^ Partsch: Klee, pp. 76–83

- ^ Giedion-Welcker: Klee, p. 161

- ^ Giedion-Welcker: Klee, p. 162

- ^ Catrin Lorch (4 January 2007). "Klees feine kleine Klumpgeister". Frankfurter Allgemeine (in German). Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 2 October 2008.

- ^ "Sammlung Prinzhorn der Psychiatrischen Universitätsklinik Heidelberg" (in German). Städtische Museen Jena. Archived from the original on 1 November 2013. Retrieved 2 January 2011.

- ^ Robert Fifty. Herbert, Eleanor S. Apter, Elise K. Kenny: The Société Anonyme and the Dreier Heritance at Yale University. A Catalogue Raisonné, New Oasis/ London 1984, p. 376

- ^ Smith, Glenn (31 May 2019). "An Interview with Frieder Nake". Arts. 8 (ii): 69. doi:10.3390/arts8020069.

- ^ Beate Ofczarek, Stefan Frey: Chronologie einer Freundschaft. In: Michael Baumgartner, Cathrin Klingsöhr-Leroy, Katja Schneider, p. 208

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Alter Klang, Impromptu per a orquestra" (PDF). iii June 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 June 2013. Retrieved eighteen December 2018.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on xxx May 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Stradivarius – The leading italian classical music characterization". fifteen April 2011. Archived from the original on 15 April 2011.

- ^ Siglind Bruhn. "Die Zwitschermaschine: Klangsymbole der Moderne". Das tönende Museum. Musik des xx. Jahrhunderts interpretiert Werke bildender Kunst (PDF) (in German). Edition Gorz. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 Dec 2006. Retrieved 3 October 2008.

- ^ Vinyl LP, Philips itemize number: PHS 600-266.

- ^ Marçal, Ricardo. Ekphrasis em música: os quadrados mágicos de Paul Klee na Sonata para violão solo de Leo Brouwer. Per Musi n. 19, january–jun 2009, pp. 47–62.

- ^ Nachi Ebisawa (18 March 2015). クローズアップ サカナクション (in Japanese). Excite. Archived from the original on 25 October 2011. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- ^ ForSchUngsmagazin. Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena. Alma Mater Jenensis, Sommersemester 1995, p. 40

- ^ Thüringer Universitäts – und Landesbibliothek – Zweigbibliothek Kunstgeschichte b2i.de. Retrieved xix April 2011.

- ^ "Die Paul Klee-Bestände im Zentrum Paul Klee" (in German). Zentrum Paul Klee. Retrieved 24 Oct 2012.

- ^ "Paul Klee's 139th Birthday". Google.com . Retrieved 18 Dec 2018.

- ^ Fayal, M.: Paul Klee: A man made in Switzerland, swissinfo, 25 May 2005. URL. Retrieved 5 September 2006.

- ^ Zentrum Paul Klee: A Swiss without a red passport Archived eighteen July 2006 at the Wayback Machine. URL. Retrieved v September 2006.

Further reading [edit]

- Berggruen, Olivier (2011). "Paul Klee – In Search of Natural Signs". The Writing of Art. London: Pushkin Printing. ISBN978-1906548629.

- Franciscono, Marcel (1991). Paul Klee: His Work and Thought. University of Chicago Press, 406 pages, ISBN 0-226-25990-0.

- Hausenstein, Wilhelm (1921). Kairuan oder eine Geschichte vom Maler Klee und von der Kunst dieses Zeitalters ('Kairuan or a History of the Artist Klee and the Art of this Age')

- Kort, Pamela (2004). Comic Grotesque: Wit and Mockery in German Art, 1870–1940. Prestel. p. 208. ISBN978-iii-7913-3195-ix. Archived from the original on 4 March 2008.

- Paul Klee: Catalogue Raisonné. 9 vols. Edited by the Paul Klee Foundation, Museum of Fine Arts, Berne. New York: Thames & Hudson, 1998–2004.

- Rump, Gerhard Charles (1981), "Paul Klees Poetik der Linie. Bemerkungen zum graphischen Vokabular ". In: Gerhard Charles Rump: Kunstpsychologie, Kunst und Psychoanalyse, Kunstwissenschaft. Olms, Hildesheim and New York. pp. 169–185. ISBN iii-487-07126-6.

- Sorg, Reto, and Osamu Okuda (2005). Die satirische Muse – Hans Bloesch, Paul Klee und das Editionsprojekt Der Musterbürger. Nix Zürich (Klee-Studien; 2), ISBN iii-909252-07-9

- Paul Klee: 1933, published past Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich, Helmut Friedel. Contains essays in German by Pamela Kort, Osamu Okuda, and Otto Karl Werckmeister.

- Werckmeister, Otto Karl (1989) [1984]. The Making of Paul Klee's Career, 1914–1920. University of Chicago Printing, 343 pages, 125 halftones.[ ISBN missing ]

External links [edit]

| | Wikiquote has quotations related to: Paul Klee |

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paul Klee. |

- Paul Klee'south Cats

- Publications by and virtually Paul Klee in the catalogue Helveticat of the Swiss National Library

- Zentrum Paul Klee – The Paul Klee museum in Bern

- Scans of pages of Paul Klee's notebooks from the Zentrum Paul Klee

- Electric current exhibitions and connection to galleries at Artfacts.Internet

- "Creative Credo" – by Paul Klee, 1920

- Paul Klee at the Museum of Modern Art

- Paul Klee at The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA)

- Biographie Paul Klee (in French)

- "Paul Klee", Der Ararat, Vol. 1, 2d Special Number, edited by Hans Goltz, Munich, May–June 1920

mcmillanbultempap.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Klee

0 Response to "What Style of Art Was Paul Klee Known for What Style Was Paul Klee Known for"

Post a Comment